The Dr. John Patrick Bioethics Column: Medicine in Times of Public Crisis

Public health and traditional medicine have a serious logical conflict. Public policy decisions must be made in utilitarian terms, unlike medicine, for populations and not individuals. Decisions are made according to which action saves the most lives. All public health policies are tradeoffs in the context of having incomplete data and finite resources. In contrast, patient-based medicine asks, “What is best for this patient?”

Public health and traditional medicine have a serious logical conflict. Public policy decisions must be made in utilitarian terms, unlike medicine, for populations and not individuals. Decisions are made according to which action saves the most lives. All public health policies are tradeoffs in the context of having incomplete data and finite resources. In contrast, patient-based medicine asks, “What is best for this patient?”

The culture of medicine was conservative for much of its history. It was not until the 1860s that it became rational to go to the doctor in terms of outcome. Before the 1860s, the iconic picture of a physician depicted him sitting, head-bowed, beside a sick child unable to do anything except be there in the crisis and pray. That behavior bred respect, which included a respect for real knowledge, grounded in experience. In the past, people went to the doctor because they knew they were sick and wanted to know what they should do.

We all deeply need to do what is right. Ordinary people are, and rightly so, not impressed by academics who say, there’s no real right and wrong, it’s all personal—patients know differently. They have expectations of the doctor, expectations that have taken centuries to come about, as, indeed, all great ethical traditions do. Change is not achieved by listening to lectures but by inhabiting stories with meaning. Our stories have predominately come from the stories of the Bible, which are not didactic in the sense of rules but provide examples of how to bear our burdens and perform our duties. The long history of physician-patient interactions within communities bred respect for older physicians, who, in turn and without thinking, set the tone for practice. I have quoted Michael Polanyi on this point before, but I will do so again, because we need to have this written on our hearts if our profession is to survive. Polanyi writes:

“…the adherents of a great tradition are largely unaware of their own premises, which lie deeply embedded in the unconscious foundations of practice… If the citizens are dedicated to certain transcendent obligations and particularly to such general ideals as truth, justice, charity, and these are embodied in the tradition of the community to which allegiance is maintained, a great many issues between citizens…can be left—and are necessarily left—for the individual consciences to decide. The moment, however, a community ceases to be dedicated through its members to transcendent ideals, it can continue to exist undisrupted only by submission to a single center of unlimited secular power.”[1]

History matters. Surely we can all see this disastrous direction in the COVID-19 public health policies which exist not by our choosing, but by political opportunism using the narrow vision of reductive science. Epidemiology and public health policy became scientific when physician John Snow investigated a cholera outbreak by using the streets of London as his laboratory. He could not have known he would become the father of epidemiology with its utilitarian ethics. The medical establishment in the 1860s was grudgingly forced to take note, but they refused to give up the ancient concept of humours being the real cause of cholera. They were soaked in Aristotelian and Hippocratic scientific error and paradoxically not sufficiently aware of the wisdom of these ancients. They behaved as though they were in the pre-scientific world where purpose was real and knowable but were dragged along by a science which denied purpose any role. They certainly did not conceive of our age of identity politics, where designated victim groups determine what matters in politics and the aim is to do so by manipulating feelings. As C.S. Lewis put it long ago, “On this view, the world of facts, without one trace of value, and the world of feelings, without one trace of truth or falsehood, justice or injustice, confront one another, and no rapprochement is possible.”[2]

Experience is important. To take the discussion further, I will recount two episodes from my own experience. The first was watching a wonderful public health system swing into action when I diagnosed the last case of spontaneous smallpox in Europe. I had the privilege of watching the public health machine smoothly respond, despite not being used for this disease in more than 10 years. The second, in contrast, is the saddening lack of response to the research in Jamaica. I was part of a program which lasted about a quarter of a century. Its purpose was to understand the pathophysiological consequences of severe malnutrition and to work out the most efficient resuscitation program. It was successful. It took the prognosis for severely malnourished children (10-pound 2-year-olds, with or without oedema) from near 50 percent mortality to zero. Sadly, in the subsequent 40 years, I have yet to find either a mission hospital following this protocol or convincing evidence that nutrition education programs have worked. Why?

Cultural context is important. Science alone is not enough, and failure to realize this is to be guilty of unthinking reductionism and fatal historical ignorance. The first example resulted from programs set in place in society where a Judeo-Christian story had been operative for 2,000 years, and its do’s and don’ts were not taught explicitly but caught from the story. The second example made the fatal presumption that science was all we needed, and it was not. Malnutrition happens predominantly in societies where evil spirits are the primary way of explaining disease. As one intelligent African said to me, “An evil spirit took my child’s appetite away, so I paid the witch doctor, but he didn’t succeed.” Don’t laugh at that story! The belief in evil spirits has given structure to a society, just as humours did to medicine for centuries. Little immediate evidence for the God of love is present in the lives of countless Africans, but the church is growing. However, the Christian story has yet to dominate the African mind. It took more than 400 years for it to happen to us, and the way this happens starts with the biblical stories we tell to our children.

Australian atheistic philosopher David Stove understood the process when he wrote: “All ideas have a context and intellectual supporters who have a vested interest in maintaining the dominance of their views.”[3] Physicians were comfortably settled in Aristotelian ideas and were not in favor of change. The philosophers who produced “idealism” were highly intelligent, but their ideas were primarily accepted because they met the existential needs of erstwhile orthodox Christians, demoralized by attacks on their faith by reductive scientists in the 18th century and Charles Darwin in the 19th century. The Bible, they were told, was incapable of handling scientific progress. British philosopher Mary Midgley describes what was being promoted as “science as salvation;” naive literalists were easy targets. Stove said the flood of intellectual refugees from Christianity was truly pitiful. The burden of their biblical embarrassment had become intolerable. In attempting to ward off biological, geological and logical criticisms of the book of Genesis, they had exhausted their interpretive ingenuity and accepted frankly irrational philosophy instead.

Ordinary folks were different. The Great Awakening in England of the late 18th century had led to a non-conformist evangelical church that was not even interested in these intellectual quarrels. The Great Awakening had come to a society in crisis, where drunkenness, poverty and crime were rampant. George Whitefield and John Wesley preached the gospel of grace, and Britain was changed, first by the personal peace and joy of repentance-led conversion and then by working out their own salvation with fear and trembling. Everyone wants to believe that the horrors of pestilence, plague and war must be resolved, but there is no evidence we will ever produce a perfect world starting with fallen sinners. Conversion does not provide an immediate solution to society’s problems as Paul’s epistles continually remind us, but over time huge societal changes happen.

By the grace of God, revival in England led to the Clapham Sect, a group who understood the need to work out salvation and were eventually instrumental in abolishing slavery in the British Empire and child labor in Great Britain. They also led the reform of prisons and a growth of serious study in the churches, whose members were now encouraged to study for themselves and act on what they had learned.

The U.S. story is a little different with more emphasis on experience. The Ivy league universities, founded by Christians as seminaries, became unbelieving, secular institutions where academics worked largely to receive scholarly applause. The established roots of the schools were ripped out, because we (Christians) were unwilling to do the work to maintain them. Jesus said, “Therefore by their fruits you will know them” (Matthew 7:20, NKJV). Unfortunately, we are known for our lack of fruit. It is time for repentance and change.

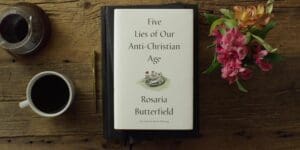

No moral consensus. As Alasdair MacIntyre said, “We have no moral consensus. Emotion and feelings are filling the void caused by the undermining of the belief in objective moral truth.”[4] As a result, particularly the young are not interested in logical argument and describe history as simply a means for patriarchal white supremacists to hold onto power. How this state of affairs happened has been elegantly described by Dr. Carl Trueman in his recent book, The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self, which I hope to write about next time. In the meantime, buy and read it, as it is a brilliant book.[5]

Learn More

Dr. Carl Trueman is a plenary speaker at the upcoming 2022 CMDA National Convention in Indianapolis, Indiana on April 21-24, 2022. For more information and to register, visit natcon.cmda.org.

[1] Polanyi, M. (1946). Science, Faith and Society

[2] Lewis, C.S. (1943). The Abolition of Man.

[3] Stove, David. (1991) The Plato Cult

[4] McIntyre, Alisdair. (1981) After Virtue

[5] Trueman, Carl, (2020) The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self