The purpose of this blog is to stimulate thought and discussion about important issues in healthcare. Opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily express the views of CMDA. We encourage you to join the conversation on our website and share your experience, insight and expertise. CMDA has a rigorous and representative process in formulating official positions, which are largely limited to bioethical areas.

App Blogs, Biological Sex, and Gender-Identity

The Anxious Generation

July 1, 2024

by Steven Willing, MD

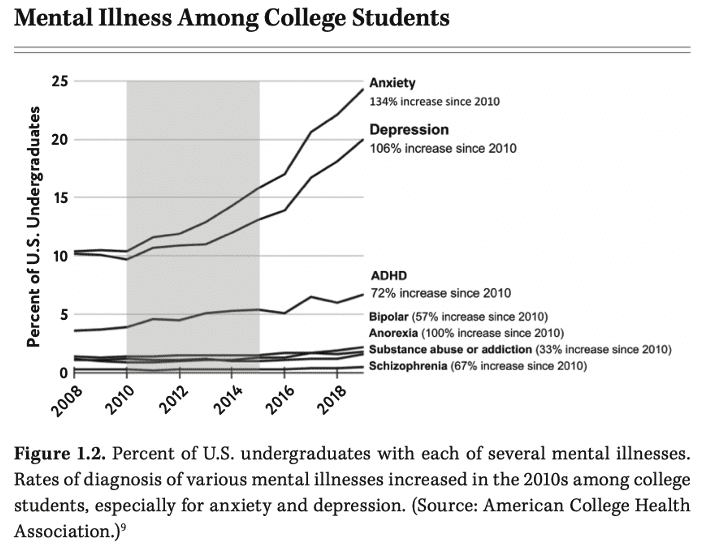

In the last 10 years, there has been an alarming rise in the prevalence of mental illness among young people throughout most of the developed world. It began well before COVID and has been observed throughout the Anglosphere (U.S., United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia) and most Western European nations. So, whatever the cause, it cannot be blamed on lockdowns or idiosyncrasies of American society.

Figure 1 The Anxious Generation, Figure 1.2, reproduced with permission

Baseline levels of anxiety and depression had been relatively stable for decades, then began to rise steeply around 2012. What happened in 2012? According to Jonathan Haidt (The Righteous Mind, The Coddling of the American Mind) and Jean Twenge (Generation Me, The Narcissism Epidemic, Generations), who are both internationally renowned social psychologists, that was the year that smartphone adoption crossed the 50 percent threshold. Let it be stipulated that correlation doesn’t prove causality, but a cliché does not grant license to dismiss. Correlation is usually the first clue to causality. Establishing causality requires two things, at least. First, other reasonable explanations should be excluded, and second, a plausible mechanism of action should be offered.

In early 2023, Haidt initiated the After Babel substack, a discussion platform for analyzing the possible relationship between mental illness and smartphone usage. This project was instrumental in leading to the publication of The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness in March 2024.

As mentioned earlier, in order to make a credible argument for causality, alternative explanations need to be ruled out. Is it just increased reporting? Was it the economy? Jean Twenge from Sand Diego State University considered 13 alternative explanations for the increasing levels of mental illness, and she effectively shows that none of them is consistent with all of the data.

In the opening chapter, “The Surge of Suffering,” Haidt maps out in detail the expanse of data showing a widespread rise of mental illness among young people. It is difficult to deny that the phenomenon is real. A number of us physicians have had ring-side seats to the spectacle.

Part two of the book, “The Backstory,” describes the rise of safetyism and the decline of traditional play-based childhood across the 90s and early 2000s. The idea of “safetyism” was introduced by Haidt and Greg Lukianoff in The Coddling of the American Mind (2018) and refers to “a culture or belief system in which safety has become a sacred value, which means that people become unwilling to make tradeoffs demanded by other practical and moral concerns. ‘Safety’ trumps everything else, no matter how unlikely or trivial the potential danger.”

Unfortunately, safetyism is counterproductive to healthy emotional development. It is reasonably well-established that children need a certain amount of independence and risk to develop self-confidence and courage. Without it, they are considerably more likely to remain immature, uncertain, anxious and fearful.

Part three, “The Great Rewiring,” shows how the vacuum left by the decline of healthy play has been filled by increasing levels of time online and alone. While internet access can be helpful for learning, research and communication with friends and family, the downside is that children are vulnerable to misinformation, disinformation, extreme forms of social comparison, overuse and addiction, pornography and predators. Only the most informed and tech-savvy parents have much chance of protecting their children from such malign influences, and only a slight chance at that. There are just too many ways to evade restrictions and access content.

The upshot of safetyism on the one hand and screen-based childhood on the other is that parents and other responsible adults overprotect in the real world but underprotect in the virtual one.

The final section includes chapters on what parents, schools and governments can do to tame the monster and restore a healthy semblance of reality to modern youth culture. Along with his collaborators, their key recommendations consist of:

-

- No smartphones before high school.

- No social media before age 16.

- Phone-free schools.

- Far more unsupervised play and childhood independence.

All four suggestions are modest and easily implemented but require a certain degree of community cooperation to implement. It would be quite difficult for parents to implement them alone, surrounded by a group culture that runs strongly in the other direction, and it would be hard on the children as well.

Spiritual Connections

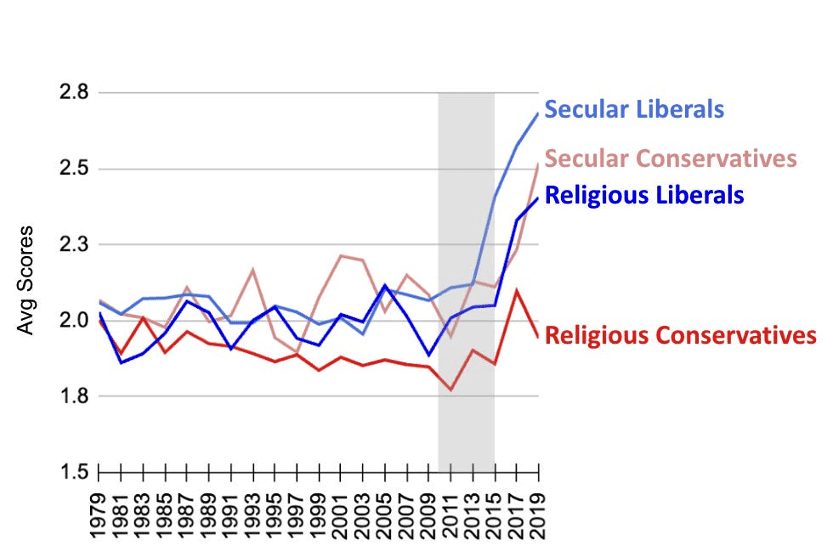

Haidt and his colleagues did identify one group of youth who experienced a much more benign trajectory over the last decade: conservative, religious young people.

A subtitle from Zach Rausch’s post on After Babel from June 10 declares unambiguously, “Religion protects young people’s mental health.” Around the world, social scientists find that religious people have lower rates of depression, anxiety, drug addiction and suicide. This chart shows how many teens experience strong negative thoughts harmful to their mental well-being:

Figure 2 “Religious teens reported fewer issues with their emotional well-being. Source: Monitoring the Future, 1977-2019

Rausch asks, “What are religious conservative teens doing differently?” He observes that conservative and religious families tend to emphasize structure and duty, while liberal and secular families tend to emphasize personal expression and exploration. (The implication for LGTBQ identification, another contributor to poor mental well-being, seems rather apparent here). Rauch hypothesizes that conservative religious parents may be more restrictive over their children’s use of technology, and data indeed shows that religious and conservative teenage girls are less likely to be heavy users of social media than their secular liberal peers.

Rauch shows that religious and conservative youth are more engaged with their local communities, have more social support, spend more time with responsible adults and enjoy more in-person time with friends.

Rauch does not suggest the actual beliefs of the religion matter, but I can think of several reasons why they would. Specific Christian teachings on marriage and sexuality oppose the pervasive lies found online. Lisa Littman and Abigail Schrier, for instance, document how internet influencers, particularly on YouTube and TikTok, recruit and seduce young women into believing they might be transgender. The transgender identity, in turn, initiates a cascade of social and psychological disruption. Religious youth are still likely to encounter such messaging, but they are also more likely to encounter counter-messaging at home and at church.

Christian (and biblical) teaching on attitudes of a healthy mind anticipated the core principles of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy by about 2,000 years. Children raised to think biblically, therefore, are less vulnerable to the catastrophizing and sense of helplessness that contribute to depression. Humility, as taught in Scripture, is a cornerstone of mental well-being.

Conclusion

In their work on After Babel, Haidt, Twenge and Rausch argue eloquently and convincingly that the dual trend of reduced free play and increased time online are detrimental to the mental and social well-being of developing young people. Healthcare professionals and church leaders need to be aware of the danger and be proactive in reducing the risk. Church youth activities can, and probably should, be made phone-free. Church and school leaders might re-evaluate their own use of WhatsApp, Instagram, Snapchat and similar tools to communicate and connect. Earlier generations got along without them and emerged much healthier.

We also must recognize that nobody is alleging that smartphones are the cause of all mental illness. Other well-established causes remain operative in putting young people at risk, particularly parenting and family structure, but also genetics (to a certain degree) and environmental influences outside the family. We shouldn’t be so fixated on the impact of smartphones that we ignore risk factors that were well-established before 2012.

For obvious partisan reasons, the media and mental health organizations are also ignoring the impact of youth and young adult THC consumption which has increased in virtual lockstep with the graphs above.